Our History is Wine ®

Virginia’s wine industry dates to the early seventeenth century when the first English settlers planted vines and made wine at the Jamestown Colony around 1608. The first settlers made wine with grapes from England, but the colonists soon became determined to grow their own grapes on Virginia soil. In 1623, the Virginia House of Burgesses enacted a law that required every householder to set aside a quarter-acre of land yearly for the purpose of growing grapes and making wine.

In 1759, a committee of the Virginia assembly was formed and charged with the question of economic diversification, a question made urgent by the depression in the tobacco trade. As its chairman, Charles Carter entered into correspondence with Peter Wyche in London, chairman of the agriculture committee for the Society for the Encouragement of the Arts, Manufacture, and Commerce (now the Royal Society of Arts), which offered awards for various desirable enterprises in the colonies, among them vine growing and winemaking. Carter’s correspondence reveals that the prospects and methods for the cultivation of the grape in Virginia were an important subject.

Charles Carter, 5th child born of Colonel Robert “King” Carter and Elizabeth Landon-Wells was born in Lancaster County, Virginia, and resided in Lancaster and King George County, Virginia. “King” Carter’s wealth came from service as land agent for the English Proprietor, Lord Fairfax. As such, he collected rents on the millions of acres owned by Fairfax in Virginia. Politically active and instrumental in the development of trade and commerce in the colonies, the Carter family at one time owned over 300,000 acres and built numerous estate homes in Virginia, many of which remain as historic landmarks today.

By 1759, Charles Carter (as well as his brother, Landon, of Sabine Hall), had already begun grape growing at his plantation, Cleve®, located in King George County, where he made wines from both native and European grapes, and it was natural that he should have chosen commercial winemaking as one of his proposals for economic reform in Virginia.

The London society took an encouraging view of Carter’s proposals and recommended various vines and practices, including the trial of distilling brandy from the native grapes. In 1762 Carter, who by then had 1,800 vines growing at Cleve®, sent to the London society a dozen bottles of his wine, made from the American winter grape (“a grape so nauseous till frost that the fowls of the air will not touch it”: probably Vitis cordifolia is meant) and from a vineyard of “white Portugal summer grapes.” These samples were so pleasing to taste—“they were both approved as good wines,” the society’s secretary wrote—that the society awarded Carter a gold medal as the first person to make a “spirited attempt towards the accomplishment of their views, respecting wine in America.”

These were the first internationally recognized wines of America.

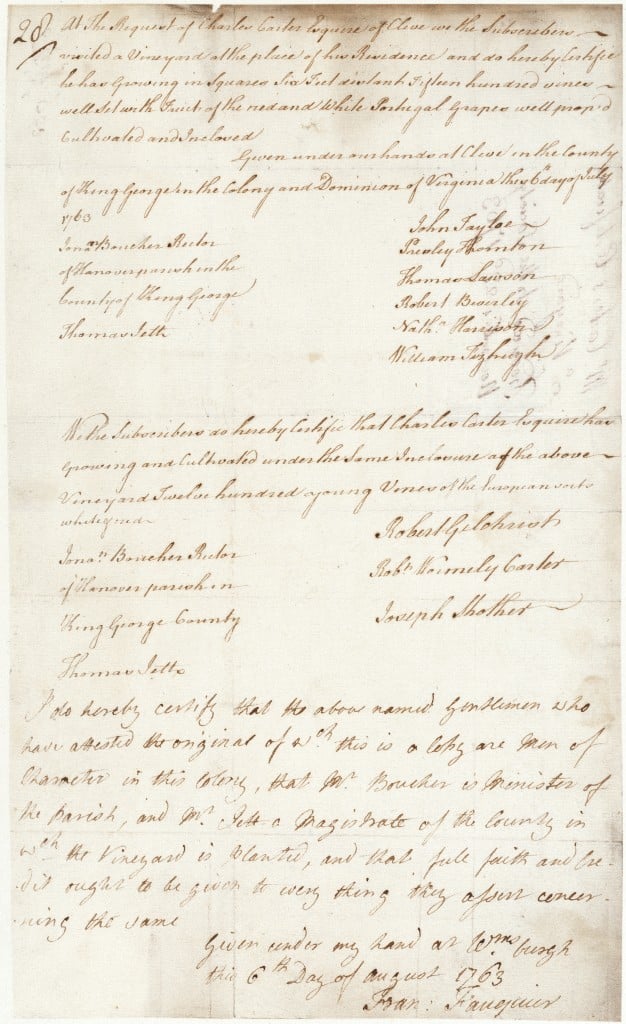

The following year, in 1763, Royal Governor Francis Fauquier, current governor of the Colony of Virginia, certified that the Carter family was successfully growing European vines at Cleve®. This is the first recorded history of successful grape production in Virginia with European vines.

In 1769, the General Assembly passed legislation called “An Act for the Encouragement of the Making of Wine.” The Carter family was instrumental in the passage of this legislation. Our country’s Founding Fathers and Sons of Virginia, Charles Carter, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison, all contributed to the development of a wine industry in Virginia through their interest in viticulture and enology. In 1773, Jefferson allowed Italian winemaker Filippo Mazzei to plant vinifera grape plants on two thousand acres adjacent to Monticello. Jefferson and Mazzei’s initial success was thwarted by the Revolutionary War and ultimately never reached fruition.

More recently, between 2005 and 2007, Philip Carter Strother, a direct descendant of the pioneering Carter family, was instrumental in the passage of The Virginia Farm Winery Zoning Act, a law intended to promote the economic vitality of the Virginia Wine Industry by restricting the ability of localities to regulate activities at farm wineries. Since 2005, the Virginia wine industry has grown from 125 wineries in 2005 to just under 200 wineries today. Within a decade of its passage, it is expected that the affect of the law will be to increase the number of wineries in the Commonwealth by over 100%.

In 2008, the Carter family returned to the production of wine in Virginia, when Philip Carter Strother founded Philip Carter Winery. Philip Carter Winery is located in Fauquier County, the namesake of Gov. Fauquier®. In the spring of 2008, 1,800 vines were planted on the Philip Carter estate in symbolic remembrance of the 1,800 vines that Carter grew in the 1700s. In July of 2009, two dozen bottles of Philip Carter wine were shipped across the Atlantic and received by the Royal Society of the Arts, UK. These wines were declared to be of the same high quality as those received by RSA in the 1700s from the Carter family. In August 2010, during an official visit to Philip Carter Winery by the First Lady of Virginia, the First Lady was presented with a gold plated, sterling silver replica of the 1762 RSA gold medal.

2012 will mark the 250th Anniversary of the first internationally recognized fine wines produced in America.

Charles Carter of Cleve Plantation, Virginia

The First Family of American Wines

Charles Carter, 5th child born of Colonel Robert “King” Carter and Elizabeth Landon-Wells was born in Lancaster County, Virginia, and resided in Lancaster and King George County, Virginia.

“King” Carter’s wealth came from service as land agent for the English Proprietor, Lord Fairfax. As such, he collected rents on the millions of acres owned by Fairfax in Virginia. Politically active and instrumental in the development of trade and commerce in the colonies, the Carter family at one time owned over 300,000 acres and built numerous estate homes in Virginia, many of which remain as historic landmarks today.

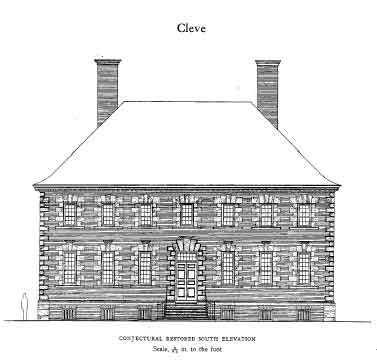

In 1754, Charles Carter built Cleve Plantation and its magnificence vied with seats of his brothers, John of Shirley, Robert of Nomini, Landon of Sabine Hall, and with the homes of his sisters, Anne of Berkeley and Judith of Rosewell.

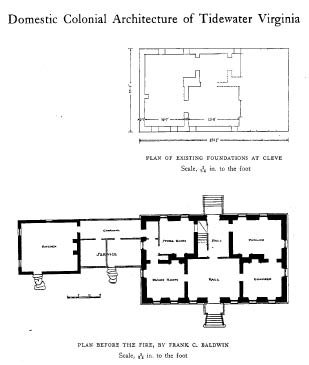

Cleve posed an imposing exterior, inspired by English designs of the type published by architect James Gibbs, and aptly conveyed the Carter family’s sophisticated tastes. Cleve differed from other brick dwellings of Virginia in surpassing them all in richness of stone dressings. At Cleve stone was found in all of the architectural features: the water-table, window arches, sills and jambs, doorway and quoining of the corners.

Cleve was celebrated for its fine collection of Georgian portraits. Rows of Carters looked down on the many generations that passed through the great hall. Three times married, first to Mary Walker, then Anne Byrd, and Lucy Taliaferro, Charles Carter had a total of 3 sons and four daughters. In his will written in 1762, Charles Carter stipulated that his sons learn “languages, mathematicks, philosophy, dancing and fencing” and that they be put with a practicing attorney until they arrive at the age of 21 years and 9 months. Carter’s daughters, on the other hand, were to be “maintained with great frugality and taught to dance”.

A fire in 1800 destroyed the Cleve interior after only a half-century of use but left the brick and stonewalls standing. A second fire in 1917 caused the demolition of the rebuilt structure. Cleve’s plan is known from surviving foundations and from photographs of the exterior taken before the second fire.

In 1759, a committee of the Virginia assembly was formed and charged with the question of economic diversification, a question made urgent by the depression in the tobacco trade. As its chairman, Charles Carter entered into correspondence with Peter Wyche in London, chairman of the agriculture committee for the Society for the Encouragement of the Arts, Manufacture, and Commerce (now the Royal Society of Arts), which offered prizes for various desirable enterprises in the colonies, among them vine growing and winemaking. Carter’s correspondence reveals that the prospects and methods for the cultivation of the grape in Virginia were an important subject. Carter had already begun grape growing at Cleve, where he made wines from both native and European grapes (it is said), and it was natural that he should have chosen commercial winemaking as one of his proposals for economic reform in Virginia.

The London society took an encouraging view of Carter’s proposals and recommended various vines and practices, including the trial of distilling brandy from the native grapes. In 1762 Carter, who by then had 1,800 vines growing at Cleve, sent to the London society a dozen bottles of his wine, made from the American winter grape (“a grape so nauseous till frost that the fowls of the air will not touch it”: probably Vitis cordifolia is meant) and from a vineyard of “white Portugal summer grapes.” These samples were so pleasing a taste—“they were both approved as good wines,” the society’s secretary wrote—that the society awarded Carter a gold medal as the first person to make a “spirited attempt towards the accomplishment of their views, respecting wine in America.”

Visitors to Philip Carter Winery are invited to view an authentic replica of the 1762 gold medal presented to Mr. Carter by the Royal Society, read his correspondence with the Royal Society on display in the Cleve Hall tasting room, and enjoy our premium wines that are produced in honor of Charles Carter’s dream for Virginia begun roughly 250 years ago

Read more about the history of winemaking in Virginia, including Charles Carter.